The History of Pearls

The pearl’s allure has endured throughout history. Long

before the development of pearl culturing, molluscs were

producing natural pearls on their own. One of the most

extraordinary of them was the Hope Pearl. It’s the largest

know natural pearl, weighing 1800 grains (3oz). At its

widest point, its circumference is 4.5 inches. It resided in

a private collection in the 1800s, capped with a crown of

red enamelled gold set with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds.

It surfaced again in 1974, when it was offered for sale at

$200,000.

Most natural pearls are much smaller than the Hope. But this

doesn’t take away from the biological miracle of pearl

formation. Today, cultured pearls outshine their natural

counterparts in both availability and marketability. But it

was the mystique of natural pearls that inspired the

development of pearl culturing.

A thousand years before the birth of Christ, ancient

civilizations along the Nile fashioned iridescent

mother-of-pearl into simple ornaments. But ancient cultures

farther east discovered thee gem within the shell: the

product of the massive oyster beds that had been quietly

flourishing in the waters of the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, and

Indian Ocean for millions of years.

Cultures of the Middle East and Asia glorified the pearl

into a symbol of wealth, status, and virtue. From 599 to 300

BC, the powerful Persian Empire celebrated its wealth by

draping its rulers with pearl-studded robes and ornaments.

Their prominent display meant that Persia’s natural pearls,

and the value humans placed on them, could not stay hidden

from the outside world for long.

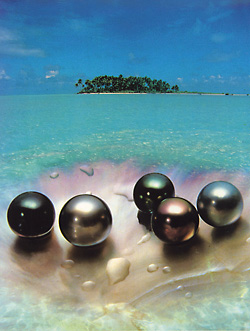

The people of ancient China, Japan, and the Pacific Islands

had been harvesting natural pearls of their own. China

fished its rivers and lakes, while Japan and the Pacific

Islands found pearls in the seas lapping their coast-lines.

When Alexander the Great’s east-west trade routes reached

the Orient, its people, already rich in native pearl

treasure, saw foreign pearls for the first time.

By 200 BC, east-west traders had established the great silk

roads to and from China. China satisfied the growing demand

for Chinese silk, jade, and other products, and used its

increased prosperity to buy Indian and Persian pearls. For

centuries, Chinese courts sagged under the weight of pearl

ornaments.

The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire of the first century BC was no stranger to

excess. As Rome’s power grew, so did its unquenchable thirst

for the pearls cherished by the Egyptian and Greek

civilizations they conquered.

When countries fell to Rome, their treasures also went to

the Romans. Roman lust for pearls was even a factor in

conquering other areas. Julius Caesar may have targeted

Britain for invasion because he suspected that region of

having natural pearl resources.

In the sixth century, the Byzantine cit of Constantinople

replaced Rome as a cultural capital. It also inherited the

Roman Empire’s wealth in the Persian Gulf. Byzantine

Christians adopted pearls as symbols of religious faith and

purity, and liberally decorated their churches’ religious

articles with the natural gem.

European

royalty became as obsessed with the gem as their Perisian

and Roan counterparts had been centuries before. During the

Renaissance, which lasted from the 1300s to the 1600s,

European rulers acquired pearls hungrily, showing off their

lavish collections at public functions. Thee gowns and hair

of England’s Queen Elizabeth I were nearly obscured by

mounds of pearls to impress rivals and dazzle those of

lesser status. European

royalty became as obsessed with the gem as their Perisian

and Roan counterparts had been centuries before. During the

Renaissance, which lasted from the 1300s to the 1600s,

European rulers acquired pearls hungrily, showing off their

lavish collections at public functions. Thee gowns and hair

of England’s Queen Elizabeth I were nearly obscured by

mounds of pearls to impress rivals and dazzle those of

lesser status.

In the 1860s, excited Europeans learned of untouched pearl

sources in the warm southern waters off Australia. Employing

Australian aborigines as divers, the British profited from

the new supply of mother-of-pearl shell, which they used for

buttons and inlay work. The naturally occurring pearls were

a lucrative bonus.

Several discoveries of high quality natural pearls in North

American rivers set off local pearl rushes in New Jersey and

Ohio river towns. One of the most famous discoveries was a

large freshwater natural pearl discovered in 1857. The

treasure eventually found its way to the collection of

France’s Empress Eugenie.

Natural Pearls Today

Natural pearls today are no longer abundant in the world’s

oceans, lakes, and rivers. However, some natural pearls

centuries old have survived decay and still shine in museum

display cases or the jewelry collections of people who are

lucky enough to own them.

New natural pearls are rare. Fine quality natural pearls are

even more so. These treasures are in demand among antique

dealers who need natural pearls to replace deteriorated or

cracked pearls in estate jewelry items.

The Introduction of Cultured Pearls

Pearls symbolized perfection to people in ancient

civilizations partly because the gem emerged complete and

ready to use from the shell, needing no faceting or carving.

By the 1890s, however, as natural pearl resources all but

disappeared, experiments with culturing by human

intervention got underway in earnest.

Three Japanese men responded to the public’s desire for

pearls in a time when that desire was becoming increasingly

difficult to satisfy. Tokichi Nishikawa, Tatsuhei Mise, and

Kokichi Mikimoto each contributed to the development of

modern pearl culturing techniques. Three Japanese men responded to the public’s desire for

pearls in a time when that desire was becoming increasingly

difficult to satisfy. Tokichi Nishikawa, Tatsuhei Mise, and

Kokichi Mikimoto each contributed to the development of

modern pearl culturing techniques.

Mikimoto

combined his culturing efforts with shrewd business sense,

and achieved international success. By the early 1920s, he

was marketing his cultured product worldwide. There was some

controversy, including a legal dispute, about the

authenticity of cultured pearls in relation to their natural

counterparts. But eventually the public accepted cultured

pearls. More people were able to afford lovely strands of a

gem that looked a lot like those worn by the royalty of days

past.

During the 1920s, pearls were especially popular among newly

rich Americans like the Morgans, Vanderbilts, and Carnegies,

who had made their fortunes during the industrial

revolution. The pearl, historically associated to boost

their social status. Great Britain’s Princess Alexandra,

daughter-in-law of Queen Victoria, was fond of pearls, and

her tastes influenced rich Americans anxious to imitate her. |